Symbolism In Poetry

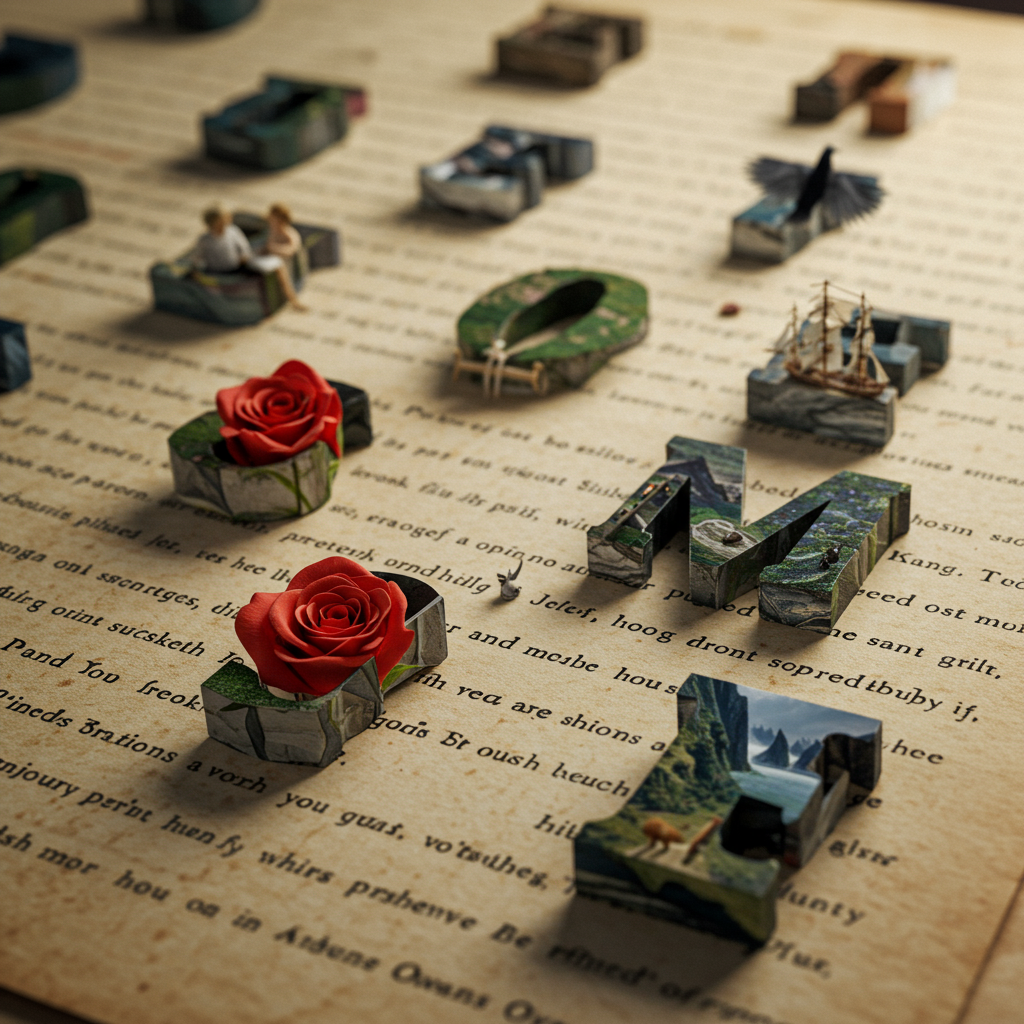

Welcome to the captivating world of poetry, where words aren’t just words—they are doorways to deeper meaning. If you’ve ever felt a poem resonate with you on an almost subconscious level, you’ve likely experienced the power of symbolism in poetry. This technique is perhaps the most essential tool a poet wields, transforming simple objects, colors, or actions into profound statements about life, death, love, and humanity.

Symbolism moves beyond mere imagery; it is the art of using one thing to represent something entirely different, often abstract. Understanding this hidden language is the key to unlocking the true genius embedded within poetic verse.

Decoding the Secret Language: Why Symbolism Matters

Poetry is inherently efficient. Unlike a novel that has hundreds of pages to explore a single theme, a poem must deliver maximum impact in minimal space. Symbolism serves as a crucial shortcut, allowing poets to convey complex ideas without lengthy explanations.

Compression and Depth

Symbolism acts as a literary time capsule. By employing a symbol, a poet can compress a vast amount of meaning—history, cultural significance, or emotional weight—into a single word. A simple mention of a “road not taken,” for instance, instantly evokes themes of choice, regret, and destiny, all thanks to effective symbolic usage.

This technique also grants the poem infinite depth. The interpretation of a symbol often changes depending on the reader’s background, ensuring that the poem remains alive and relevant across generations and cultures.

Emotional Resonance

Abstract concepts like despair, joy, or freedom are difficult to describe directly. Symbolism bridges this gap by grounding the abstract in the concrete. When a poet uses the symbol of a “caged bird” to represent oppression, the reader doesn’t just think about oppression; they feel the restriction, the desire for flight, and the frustration inherent in the image. This visual and emotional connection makes the poetry far more impactful and memorable.

The Toolkit of Symbolism in Poetry

To truly master the interpretation of verse, it helps to recognize the different ways poets utilize symbolism in poetry. Not all symbols are created equal; some are universal, others require careful contextual analysis.

Universal Symbols (Archetypes)

These symbols hold meanings that transcend culture, time, and language because they tap into shared human experiences or natural phenomena. They are the foundations upon which many great poems are built.

- Water: Almost universally associated with purification, transition, life, or rebirth. A storm might symbolize chaos, while a placid lake suggests peace or reflection.

- The Sun: Represents life, power, energy, or enlightenment. Its setting often symbolizes death, the end of an era, or descending darkness.

- Seasons: Spring signifies new beginnings and youth; winter represents death, stagnation, or old age.

Conventional Symbols (Cultural Shorthand)

Conventional symbols rely on shared cultural understanding. They are essentially cultural shorthand—specific groups have agreed on their meaning over time.

- The Dove: A universally accepted symbol of peace and hope, largely due to religious and historical context.

- The Skull: Symbolizes death, mortality, or danger.

- Colors: Red often symbolizes passion or anger; white traditionally means purity or innocence (though this can be challenged or inverted by modern poets).

Contextual Symbols (Poet-Specific)

These are the most challenging yet often the most rewarding symbols. A contextual symbol draws its meaning entirely from the surrounding poem or the body of the poet’s work.

For example, a specific type of clock might be meaningless in general literature, but if a poet continually features it near characters who are rushing or dying, the clock becomes a powerful, chilling symbol of inevitable mortality within that particular poem’s world. Pay attention to anything the poet emphasizes or repeats.

Mastering Interpretation: How to Spot a Symbol

Reading poetry is an active process. You shouldn’t just look for symbols; you should look for things that seem to carry weight disproportionate to their physical presence.

Look for Repetition and Isolation

When you read a poem, note objects or phrases that are mentioned multiple times. Repetition signals importance. Similarly, if an object seems oddly specific or isolated in the description—a single, unbroken mirror in a derelict house—it is likely meant to represent something larger, perhaps vanity, self-image, or truth.

Consider the Setting and Mood

A symbol often aligns directly with the emotional atmosphere the poet is trying to create. If the poem is mournful, and the setting features a dense, suffocating fog, the fog itself is symbolic of confusion, uncertainty, or the obscuring of truth. The physical environment mirrors the internal emotional landscape of the poem’s subject.

Iconic Examples of Symbolism in Poetry

Many famous poems owe their lasting legacy to brilliant symbolic maneuvering.

Robert Frost’s poem, The Road Not Taken, uses the divergence of two roads not merely as a scenic detail, but as the central symbol for the choices that define a human life. The entire emotional weight of the poem rests on this simple fork in the path.

In works focusing on the passage of time, such as those by T.S. Eliot, “the journey” is frequently used as a metaphor for spiritual or intellectual quest. The physical act of moving symbolizes the difficult process of growth or discovery.

Furthermore, consider the work of poets like W.B. Yeats, where objects like “The Wild Swans at Coole” symbolize an idealized, unchanging natural perfection contrasted sharply with the poet’s own aging and change. The swans become a representation of eternal grace that humanity cannot sustain.

Conclusion: The Richness of Symbolic Language

Symbolism is the heartbeat of poetic expression. It allows poetry to be simultaneously specific and universal, concrete and abstract. By recognizing and interpreting the symbolic language, you move from merely reading the words on the page to experiencing the poet’s intended vision.

Embrace the mystery; don’t be afraid to look deeper than the literal. The true magic of poetry lies in its capacity to transform a common object—a flower, a bird, or a stone wall—into a profound and lasting representation of the human condition.

*

FAQ: Understanding Symbolism

Q1: What is the difference between symbolism and metaphor?

A: Symbolism is broader. A metaphor is a direct comparison (“Life is a journey”). Symbolism uses an object or action to stand for something else, usually an abstract idea, often implicitly (“The journey began at dawn,” where dawn symbolizes a new beginning). Symbols can often function as metaphors, but not all metaphors are extended symbols.

Q2: Can an object have multiple symbolic meanings?

A: Absolutely. A symbol’s meaning is highly dependent on context. For instance, the color blue can symbolize coldness and sadness in one poem, and tranquility and truth in another. Good poets leverage these multiple interpretations to create complexity.

Q3: How do I know if I’ve interpreted a symbol correctly?

A: While there is room for personal interpretation, a “correct” interpretation is one that can be supported by evidence within the text. Look for clues: the tone, the emotional content, and how the symbol interacts with other elements of the poem. If your interpretation makes the rest of the poem make sense, you are likely on the right track.

Q4: Does all poetry use symbolism?

A: Most high-quality poetry uses symbolism to some degree, even if subtly. Even realist poetry often relies on the symbolic weight of specific locations or highly charged physical details. Poetry that is entirely literal often risks falling flat or becoming mere prose broken into lines.

*